I spent the weekend before the Fourth of July backpacking the

south segment of the

Olympic National Park coastal trail, from Oil City on the north bank of the mouth of the Hoh River to Third Beach at La Push, on the south bank of the Quillayute River. Three days of sunny afternoons, sand and tides, and a unique wilderness coast. There were just two of us, Karen and I, from the

Olympia Mountaineers who made the trip, but we were the lucky ones.

We started at the trailhead at Oil City (no city, the map has an “oil seep” marked a few miles away) on a trail that follows the Hoh River down to the ocean, where it drops you on the beach and a huge pile of driftwood, trapped between the river and ocean. A few miles of beach walking, with one small headland which we rounded on rocks, brought us to the first of the dreaded headland trails. We were fortunate: the weather had been dry for at least a week, so the trails were as non-muddy as they ever get, which is a particular blessing when climbing up the steep headland access trails.

The first headland climb, up to the trail passing Hoh Head, was a nice introduction to the tricks of this route. It consists of three cable ladders – wood steps suspended on cables about fifteen inches apart hanging down the steep slopes. The first two ladders came one after the other and were in fair shape. The last one was nasty – steep, slippery, and missing critical rungs at the top. Still, we topped it and climbed up to the top and through some pretty woods. There were lots of downed trees on this stretch – we even lost the trail to one for a time – but soon we were past Hoh Head and walking along the top of the bank with wonderful views of the ocean, its rocks and reefs, and beautiful, blue skies and water.

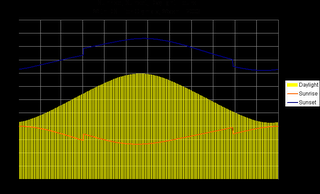

The old trail down to the beach just north of Hoh Head (which requires a quite low tide to continue north from there) was lost to a massive slide and we saw no sign of it at all. It wasn’t in our plans, anyway, because the tides that weekend were only moderate (low of one foot, high of nine feet), but were well-timed for midday. Late in the afternoon, we came across the first of the camps and descended to Mosquito Creek, where we camped. There were a small party camped in the woods, a couple camped on the beach, and, later, a group of seven hikers joined us for the night.

Crossing Mosquito Creek is one of the obstacles on this route, but presented no problems with the tide conditions and low water flow that we had. A pelagic cormorant rookery was established on the rock face of the headland to the south of our camp, with the long-necked birds constantly wheeling onto and off of the face. For a while, a falcon harassed them, but we didn’t see any other result.

The couple camped on the beach near us turned out to be Seattle Mountaineers and had noticed this hike listing, no doubt wondering how many backpackers I was going to bring them to crowd out their enjoyment. We spent part of the evening talking with them around their fire and then settled into our tents for the night.

The next morning our path took us up the beach for a couple of miles, over a headland with crossings of Goodman and Falls Creeks, and down to a camp on the beach at Toleak Point. The first beach stretch was slow going, because of the wonderful tide pool life amongst the big rocks and sea stacks left behind by the retreating tide. The trail up the bank south of Goodman Creek was better than Hoh Head’s, though the trail on top was much brushier. The creek crossings were easy, though I did manage to get water in one of my boots.

The trail down to the beach south of Toleak Point was an excellent cable ladder down solid rock. It seemed quite secure compared to some of what we’d seen. Just before we descended, we passed a couple going the other way with their golden retriever, which they’d loaded into a pack, emptied for the purpose, and carried up the ladder. (Pets aren’t allowed on the trail, but, you know, the rules don’t actually apply if you pretend to not know them or not see the hundreds of posted notices.)

There were five or six groups camped on the beach along the south side of Toleak Point and more camped in the woods on the west-facing beach north of the point. We started in the woods, but the wind was blowing right into them and the sun around the point made it feel fifteen degrees warmer, so we camped on the beach in the sun, nearer the only water. The tide came in from both sides of the point, making an interesting set of currents and flows as the two sides converged. Seals played in the water and eagles soared in the skies.

We were concerned about the group of just-short-of-middle-aged men who had sprawled their camp right on the only water source and in front of the trail to the privy. When we arrived they were drinking the biggest beers I’ve ever seen open and playing baseball on the beach. They followed this up with an enormous bonfire on the beach. Still, we were upwind and they ran out of gas early in the evening and were still getting up when we hiked out, so they weren’t a problem.

The final day offered a nice hike up the beach to Strawberry Point, where we saw more eagles and tide life, along another beach to another point which could be rounded on the rocks above the beach, to the camp at Scott Creek and the headland called Scotts Bluff. There was a large group camped there, right on the creek, as well. The trail on the south side of the Bluff was quite good – it climbed in a very civilized manner to the top, through some pretty woods – spruce and hemlock – to a very abrupt, steep clay slope, with ropes for assistance. I’m glad it was dry, for the footing was good. Wet would have been another experience.

The next leg was a short beach walk to the Taylor Point headland. The trail here was showing signs of nearing civilization. After a short scramble up a clay bank, it was solid stairs up the slope! This trail dropped back down to the beach over a couple of cable ladders in very good repair. And, then we were on Third Beach, which is well within reach of almost anyone, and it showed. There were lots of people on the beach, quite in contrast to our experience just over the last headland, and no wonder. It’s a beautiful beach, the weather was wonderful, and the parking lot is less than a mile and a half away.

We made short work of that last stretch, accompanied by the couple from Seattle, to whom we gave a ride into Forks. I’d had my car moved from Oil City by

Rainforest Paddlers, who offer a shuttle service. To my delight, my car was there. To my credit, I had a set of keys in my pack, because I couldn’t find the keys that shuttlers had used to drive the car around. To the discredit of Rainforest Paddlers, when I called them to find out where my keys were, I learned that, instead of putting them in the trunk (I had a set in my pack, remember), under the mat, as I’d asked and as had been communicated to the shuttler, she decided to put them in the “usual” place, under the bumper. So, by the time I’d learned this, they had long since shaken loose. She called it a communications break-down, in spite of admitting that she’d received the communication fully. She just decided that she knew better. I call that an error in judgment. Fortunately for future trips to the coast, there is an alternative:

Windsox Trailhead Shuttle.

Even that was nothing more than a minor irritation, given three days of sunny afternoons, dry weather, favorable tides, beautiful scenery, good company, interesting geography, topography, and wildlife.